Islam does not recognize any authority outside the Qur'an, which is considered eternal and immutable. According to fundamentalists, there is no possibility of reform within Islam. However, I believe that perhaps only one reform would suffice: the reform of its calendar. Although I cannot prove this hypothesis scientifically, I still present it to those interested in this widely controversial religion.

Unlike Islam, all other religions—including Christianity, Buddhism, Judaism, as well as various forms of paganism and animism across the globe, whether among Native Americans, Africans, Asians, or Australasians— respect the succession of seasons and the cycles of nature. These religions, in one way or another, account for the solar cycle. This is why, in the Northern Hemisphere, religious holidays such as Easter, Passover, and the Persian Nowruz coincide with the spring equinox; Pentecost (or the Feast of Saint John) and Shavuot align with the summer solstice; the Jewish New Year and Yom Kippur with the autumnal equinox, and Christmas and Hanukkah with the winter solstice. The Chinese New Year, similarly, is celebrated on the day of the second new moon after the winter solstice.

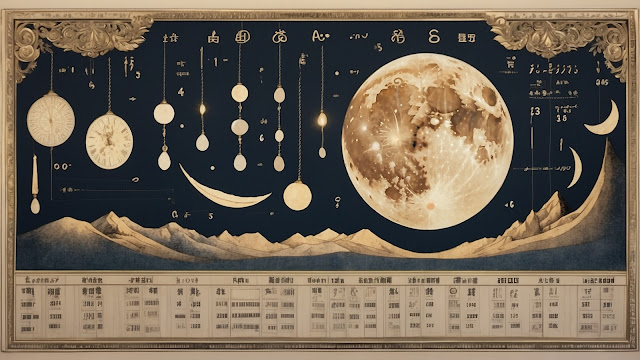

Islam, on the other hand, strictly adheres to the lunar cycle and is the only religion that follows a purely lunar calendar. Consequently, Ramadan can fall in any season, completing a full cycle across all seasons over a 33-year period.

Before the advent of Islam, the Arabs, like the Hebrews, used an intercalary month—a 13th month added every three years to align the lunar and solar cycles. This was necessary because the lunar year (with each month averaging 29.5 days) is approximately 11 days shorter than the solar year. To correct this discrepancy, they added a 13th month every three years, a practice observed in the Jewish calendar. These years with an extra month are known as embolismic years. The determination of this 13th month was often done empirically and sometimes arbitrarily, which had significant consequences in tribal Arabia, a region lacking a centralized state. There was only one continuous truce period each year, lasting four months, during which people could safely undertake pilgrimages, trade, and travel without fear of being robbed, raped, or murdered by rival tribes.

According to Maxime Rodinson, Muhammad received numerous complaints from individuals who believed they were traveling during a truce period, only to be attacked by others who claimed that the period had ended due to disagreements over whether the year was embolismic. To resolve this issue, Muhammad abolished the 13th month (referred to as Nassi in the Qur'an), likely without fully understanding the astronomical consequences. Since he only lived a few years after this ban, the long-term implications were not immediately apparent.

According to sources cited by Ibn Warraq in Why I Am Not a Muslim (1995), Muhammad himself violated truce periods and eliminated the embolismic month to justify his actions. The chronology of Al-Azhar seems to support this theory, as the verse abolishing the embolismic month is found in the penultimate Surah of the Qur'an.

Even though some religions, like Christianity and Judaism, partially observe the lunar cycle when determining the dates for Easter and Passover, all other religions also respect the solar cycle. This is true for Mayans, Incas, Egyptians, Persians, the builders of Stonehenge, Hindus, Buddhists, Confucianists, Jews, Christians—everyone except Islam.

Sharia law is considered to be above not only the laws of liberal democracy, but even the laws of nature itself.

My Chronopsychological Hypothesis

The influence of time-related changes on health, behavior, mood, and cognition is well-documented. Intraday disruptions, such as those caused by jet lag, can significantly affect well-being and may require hours or even days to fully recover from.

For individuals who frequently experience jet lag—such as commuters traveling regularly between Los Angeles and Tokyo—these disruptions can lead to chronic issues. Repeated exposure to such drastic time shifts may contribute to persistent sleep disorders, eating disturbances, and alterations in normal brain activity.

Psychiatrists have identified Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) as a type of depression that manifests primarily during winter when the nights are longer.

Gustavo Bruzual, an old schoolmate of mine who became the director of Venezuela’s main astronomical observatory, wrote his doctoral thesis on the variations in solar activity. He explained to me how these variations were correlated with changes in mood and behavior.

We all know that there are days when people seem more cheerful and days when they do not. Studies conducted in institutions for children with developmental disabilities have recorded days when the children were collectively more agitated and days when they were calmer. The data showed that these agitated and calmer days coincided globally, from Sweden to Patagonia, from Japan to Spain. These patterns were correlated to variations in solar activity.

Having a time reckoning system that does not take into account the influence of the Sun on nature could have some unsettling effects. The fact remains that only Islam adheres to such a system. If it were a beneficial approach, other cultures or religions might have adopted it, yet for all non-religious purposes, Muslims use the Gregorian calendar.

I cannot prove my hypothesis because it can't be validated experimentally. However, I see no reason to assume that the fact that Ramadan and all other Muslim festivities shift 11 days earlier each year has no impact on the collective and individual psychology of the believers in this religion.

_____________________________________________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Court de Gébelin, A. (1776), Monde primitif analysé et comparé avec le monde moderne considéré dans l'histoire civile, religieuse et allégorique du calendrier ou almanach.

- Goldziher, I. (1920) Die Richtungen der islamischen Koranauslegung

- Halévy, J. (1883) Mélanges de critique et d'histoire relatifs aux peuples sémitiques

- Hommel, F. (1901) Der Gestirndienst der alten Araber

- Horten, M. (1913) Texte zu dem Streite zwischen Glauben und Wissen im Islam

- Ives Curtiss, S. (1902) Primitive Semitic religion today

- Krehl, L. (1863) Ueber die Religion der vorislamischen Araber

- Lewis, B. (2010) Faith and Power, Oxford University Press

- Lewis, B. (1984) The Jews of Islam, Princenton University Press

- Lammens, H. (1914) Le Berceau de l'Islam, l'Arabie occidentale à la veille de l'hégire

- Mervin, S. (2010) Histoire de l'Islam : Fondements et Doctrines, Flammarion

- Margoliouth, D. S. (1914) The early development of Mohammedanism

- Nielsen, D. (1904) Die Altarabische Mondreligion

- Nilsson, M. P. (1920) Primitive time-reckoning

- Prémare, A-L. (2005) Les fondations de l'Islam, Seuil

- Troels-Lund, F. (1908) Himmelsbild und Weltanschauung im Wandel der Zeiten

- Warraq Ibn (1995) Why I'm not a Muslim

- Wellhausen, J. (1883) Reste arabischen Heidentums (Last but not least)

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire